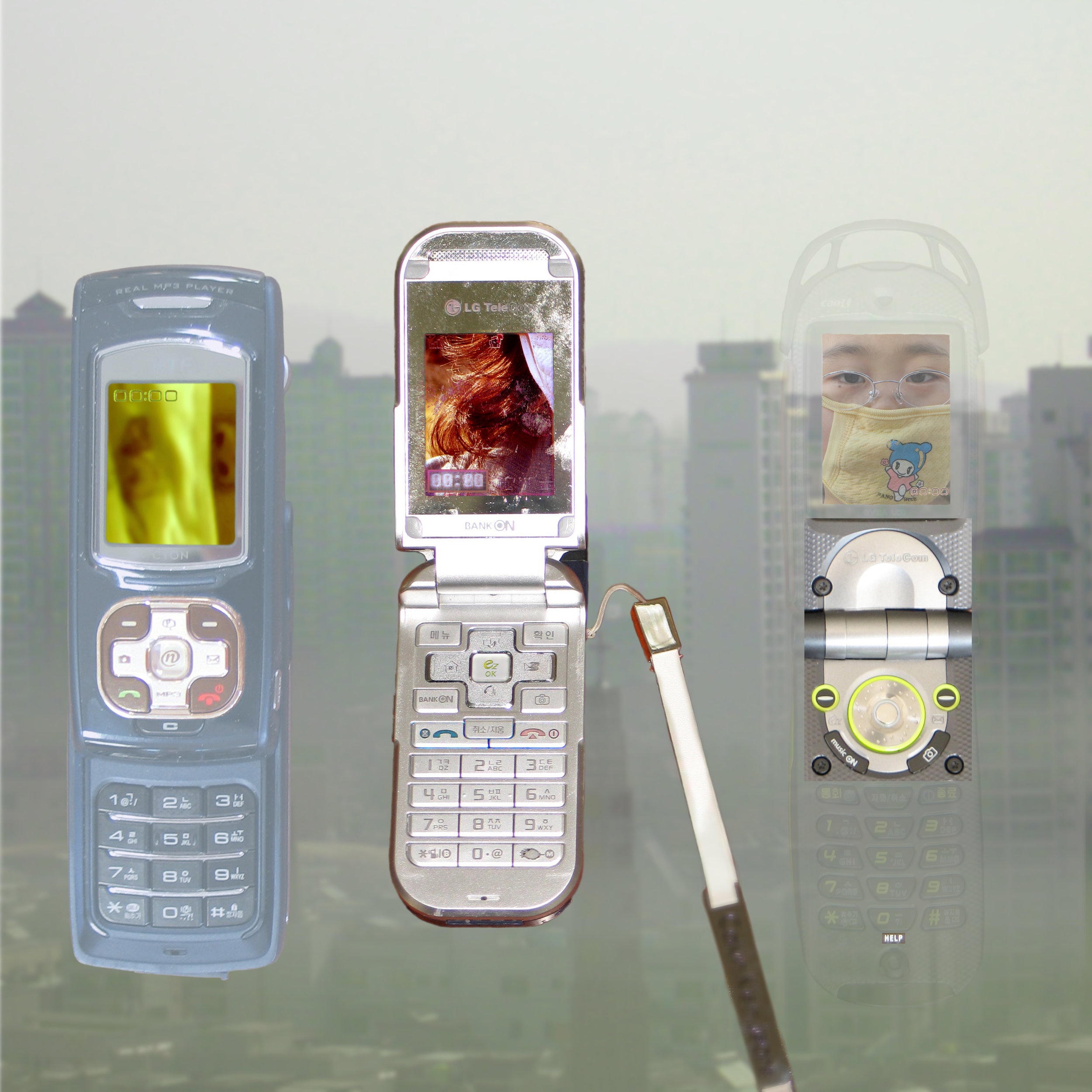

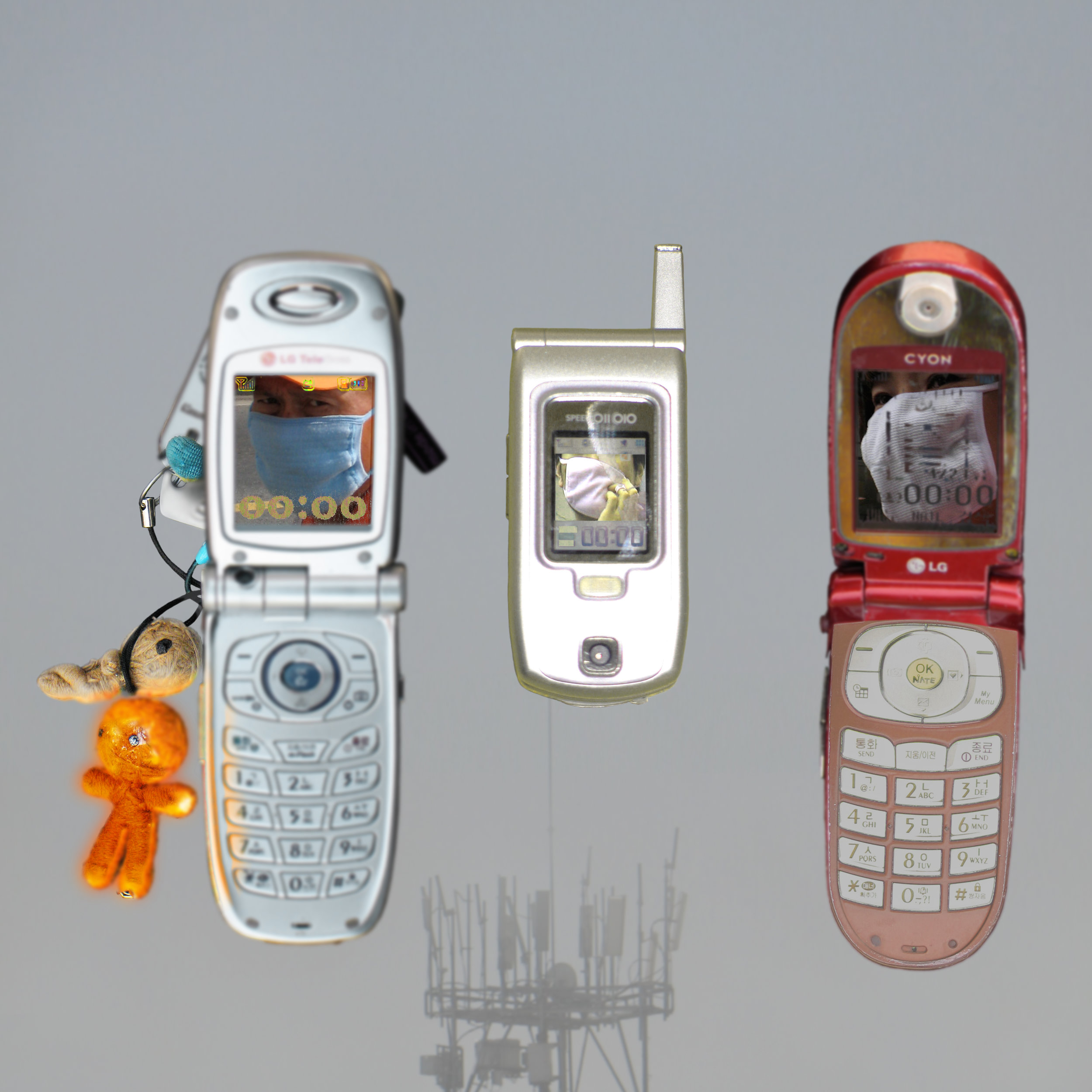

AIRBORNE, 2008

Metallic C-prints, 36 x 36 inches each

Mobile phones affirm and deny what is immediately present before us. They carry images and sounds customized to represent individual callers, however remote. We believe that they offer protection and lessen fear, especially fear of another’s aggression, address, glance or absence. Their capabilities provoke meditation on degrees of immanence through an amalgamation of personal and public space. When speaking on a hand phone, one typically looks down, withdrawing from the immediate environment. The proximate withdraws from consciousness as the distant approaches, as in any telecommunication, but now, the more comfortable we’ve become speaking privately in public space, this creation and collapsing of relations is on constant display.

Airborne further emphasizes communication by visualizing its lack, through the muzzling motif of masks. Dust masks, common on the spring streets of Seoul and other cities, are social shells that conceal and reveal collective contamination and individual sacrifice. They isolate and bind and make anonymous. Often they are worn by the sick so as not to spread disease. But they are also worn by protesters to preserve anonymity and for protection from dispersing fumes. Indicative of social challenge, personal vulnerability or pandemic infection (as in the case of Avian Flu or Ebola), the mask is permeated by fear floating freely between peoples, countries, and continents.

The unique and bitter history of Korea acutely exemplifies unity and division. Over the last century it has experienced the most intimate suffering among the ‘comfort women’ during the Japanese occupation, brothers caught between competing powers who fractured their country, students curtailed by a U.S. backed ‘democratic’ regime, and a society silenced in hope for economic assistance from its former oppressors. AIRBORNE offers formal and surreptitious portraits of this people. Diverse in age (from 2 to 90 years old) and profession (from maintenance workers to university professors), their faces are half-covered, half revealed.

AIRBORNE situates itself above the particular soil of the most wired country in the world and in ubiquitous political air. In cities like Seoul, high-rise perspectives are the norm – jumbles of multi-storied apartment buildings, huge telecommunication satellites and home satellite dishes, radio towers, tangled telephone lines and circuitry, air conditioners, and neon church signs amidst skies polluted with airborne particles. These aerie views become backdrops for cell phones hovering autonomously, with all their messages, texts and images, signaling the spirit of the times, and instilling the need for constant connection, while paradoxically breeding dependency amidst isolation. AIRBORNE means to leave us gasping with mouths and eyes agape.